Today my daughter turned seventeen. Right before the anniversary of the exact moment of her birth, I came blaring at her down the hallway with my recording of Stevie Nicks singing "Edge of Seventeen."

|

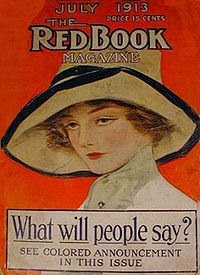

| image credit: Erik Baker |

Corny, but all the more fun as she looked up at me without moving her head, but with the classic teenage stance toward the world: a beneath the breath "Whaaat?"

|

| Repose, John White Alexander, 1856-1918 |

Many people already know the music trivia that explains the title-- that Tom Petty's wife stated in her southern accent that she had met him at the "age of seventeen". Stevie Nicks heard it as "edge" and a song was born. There are other perfect lines in this song fit for a teen's birthday, and ones that also kick up nostalgia for their babyhood, and nostalgia for our own seventeenhood.

My daughter asked me why people look back on that age as being so great and I replied that it's a strange transition in life. Your childhood is behind you, but the big unknown future has not quite arrived. You know yourself pretty well by that time and you can do so much that an adult can do such as drive a car, buy stuff with your own money, notice what you like and don't like about the opposite sex, complain about the world, and analyze your personal problems. But there is also still a great deal of innocence that lets you get away with so much without worry and you can respond to your prospects with a bemused "I don't know."

As an adult who still doesn't know as much as I need to, and who often feels like a bewildered but hopeful seventeen year old, I need regular reminders of the power of that transitional time. For a while, I had these two lines from the "Edge of Seventeen" posted on my laptop where I could see them as a daily nudge to return briefly to that inspired yet innocent frame of mind; the one that is so hard to find on some days as an adult with the pressing demands that began in the past. Even if it is a pop song from the eighties, these lines stand outside of it for me, as the stance that everyone should be in toward those who more practiced:

"When I see you doing what I try to do for me

With the words from a poet

And the voice from a choir

And a melody

Nothing else mattered."

A lot matters to me besides my own creativity. Being an artist and a hard worker isn't a pass for egomania. But there are moments in any kind of meaningful work when they really do need to feel like nothing else matters, because this is what you do, and is one of many important reasons why you are here.

Note: a funny thing happened on the way to the big moment of my daughter turning seventeen. As I was doing a little dance for her along with the song, I noticed that my foot was bleeding and leaving small dots on the floor. I checked to see a tiny grain of glass that had embedded itself into the ball of my foot and I laughed. If I needed a salient reminder that I am the mother and not the innocent baby, and not the seventeen year old in bloom, that did it. There will always be a tiny embedded pain in my heart as they fly off and do what they need to do as if nothing else matters.

_06.jpg)